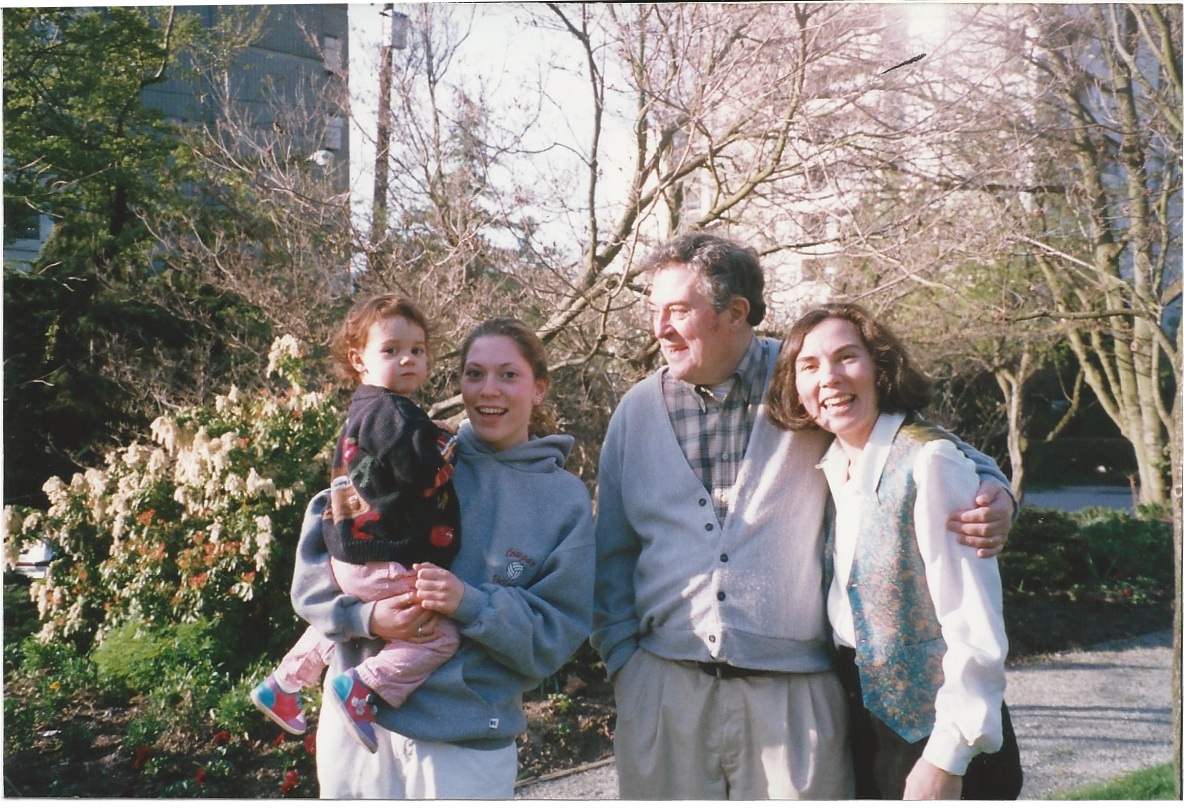

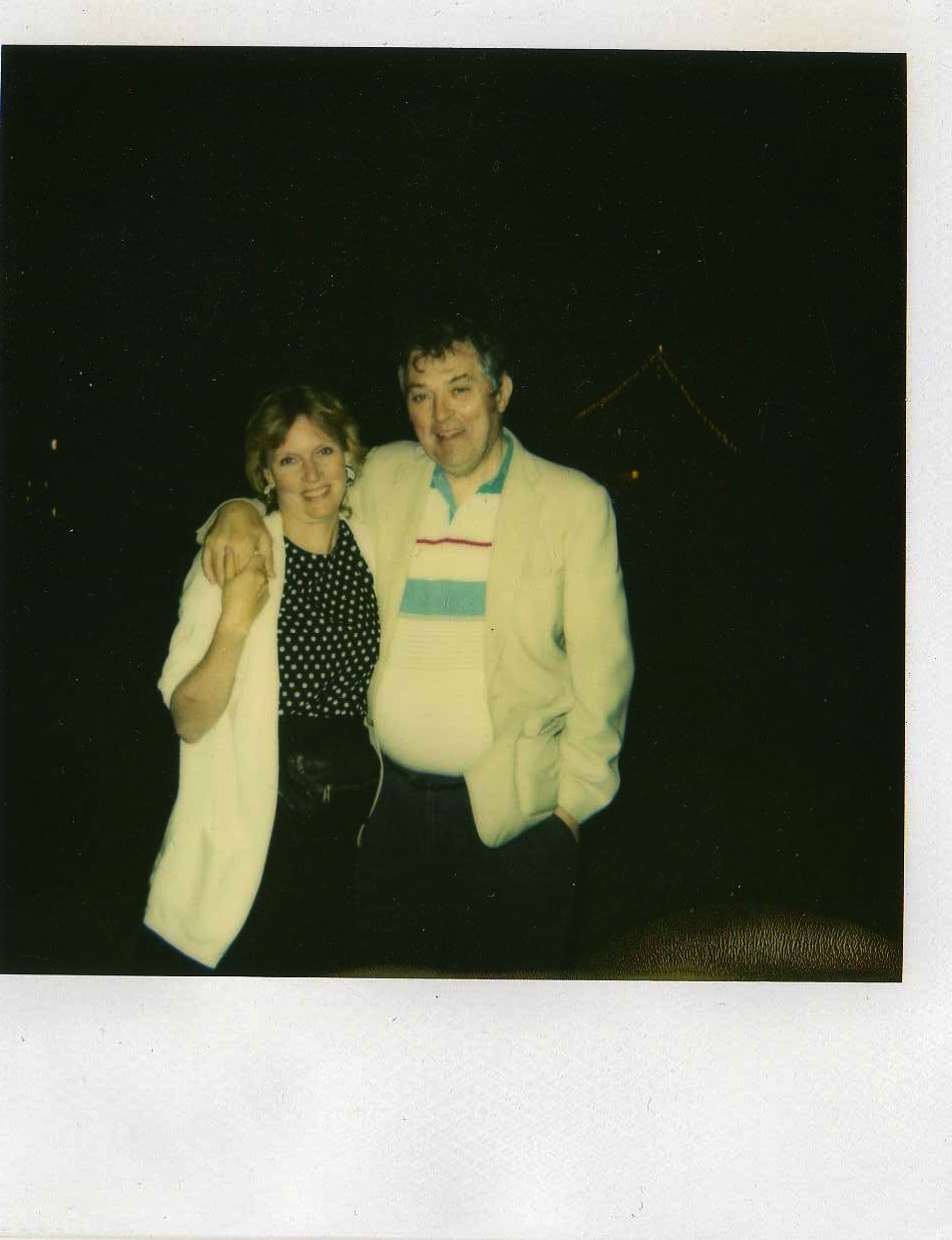

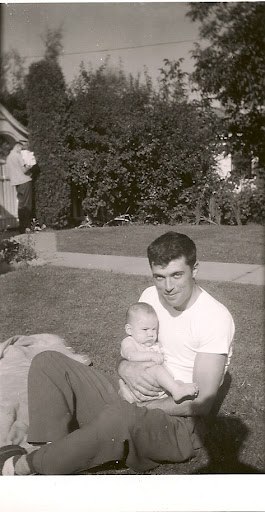

It’s Saturday in Prague. It’s also Valentine’s Day, a day which marks the two year anniversary of the death of my father. But I don’t think that’s particularly sad. Not the fact that Dad died, which, of course, is sad, but the fact that he died on Valentine’s Day. I think the date of his death is symbolic of the love he had for his children, and of the fact that he passed peacefully and quickly, in his sleep, after a battle with cancer. I think the fact that his death was as quiet and as gentle as it was when it could have gone so differently was a gift – from him, from God, from the universe, from fate, from whatever force it is that was working its cosmic magic. I consider his love a gift, his life a gift, and the peace we made before he died the ultimate gift.

But I didn’t set out to write a post about my father (I did that more eloquently last year, here), only to acknowledge that today, as I pass another day in this mysteriously beautiful city, so far away from home in the middle of a stark, cold European winter, I have been thinking about him. And I have been thinking about love.

Ever since they died, I have been trying to strike a balance between the parts of my mother and father that are contained within me, of which there are a great deal. Sometimes I feel their echoes in my worst behaviors. But often, I recall the good in them and I aim my aspirations in that same direction.

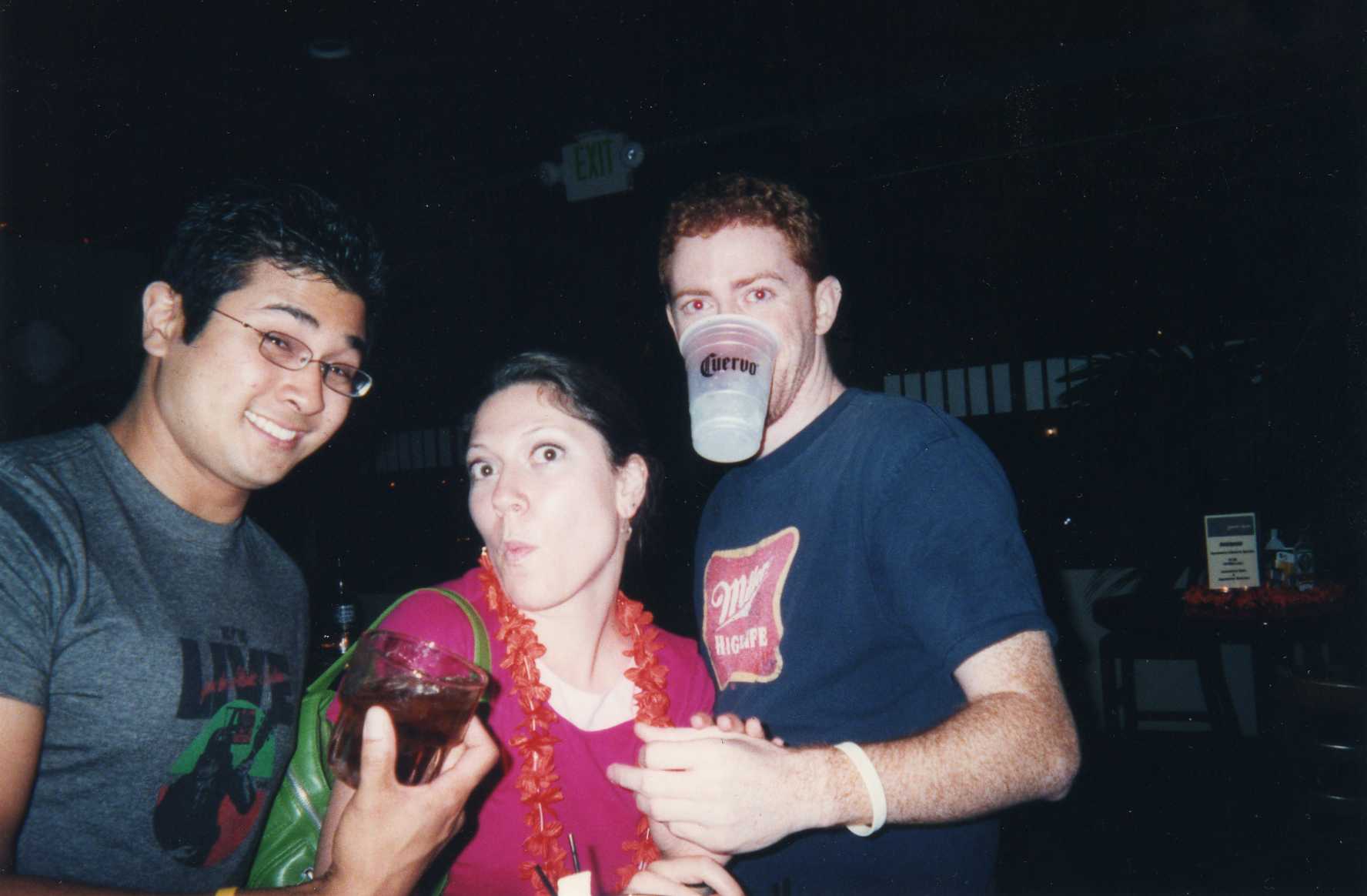

Dad was adventurous, bold. I think he’d be proud of me for taking this trip to a far off, foreign place all by myself. For unapologetically shrugging off the curious glances when I sit down to a meal or sip espresso while journaling in a café or drink cognac in the hotel bar, alone. Leave it to other people to cling to the security of another body. I don’t mind being on my own, and during my travels, I have found that I am, in fact, quite good company.

I think Dad would be proud of my hotel choice, as well. Dad always liked to go big, and my hotel does not disappoint. It’s a sleek, modern, five star European beauty located in Stare Mesto – Old Town – within striking distance of the main square, the Vltava River and the Charles Bridge and just down the hill from Mala Strana (“Little Quarter”), a steep hill leading up toward Prague Castle and breathtaking views of the city seen from on high.

My hotel is central and yet, it’s removed from the madness at the end of a quiet street – Parizska (“Paris”), aptly named for the posh luxury boutiques that populate it; brands like Cartier and Porsche Design and Dolce and Gabbana and Escada and Tod’s of London and the like.

I couldn’t believe in my wildest dreams that I could afford such a hotel, with its spectacular gym and spa – no joke, it rivals some of the gyms I’ve seen in L.A. with its aerobics garden, weight room, cardio room, stretching room, enormous glass roofed swimming pool, sauna, luxurious showers and spa treatment rooms – its rooftop restaurant, cozy lounge bar, buffet breakfast overlooking the Vltava River, its opulent guest rooms with spacious marble-tiled bathrooms, Tempur-Pedic mattresses, customized pillow menu (you can choose from six different styles, adjusted to your comfort), and satellite television with channels in six different languages. Oh yeah, and there’s the breathtaking view of the gothic buildings in Old Town Square as seen from out the window of my 7th floor room, courtesy of an upgrade from the handsome hotel desk manager. Simply because I told him this was my first visit to Praha.

This is definitely the fanciest hotel I have ever stayed in, but because the dollar is strong right now, especially against the Czech Crown (Korun), and it’s the middle of winter and bitterly cold, and I got a cheaper rate for staying six nights, I am actually paying less per night for a five star hotel in a European capital than I have spent to rent a room in a Best Western. Ridiculous. And wonderful. And anyway, who cares that it’s freezing outside? I never want to leave the confines of this glamorous hotel, with its well-heeled, fur-swathed, international clientele.

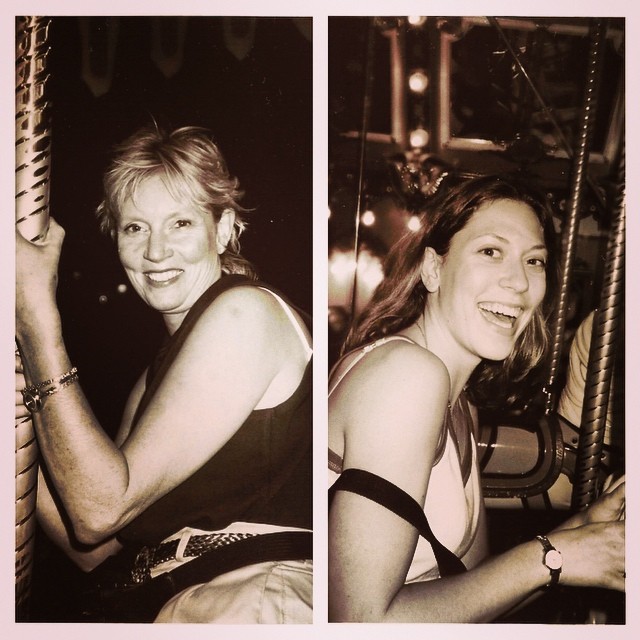

But leave the hotel I have, to explore this gothic city, to climb the hills, to wander the cobblestone streets, to gape at elegant centuries-old buildings with cheerful watercolor facades. I came here with no plan as to how I would spend my time, which is pure my mother and so very unlike me. When mom traveled, she hated to be rushed or kept to an agenda, preferring instead to laze about her hotel room for hours. This behavior drove me – the compulsive planner – insane, but mom could care less about cramming in touristy, sightsee-y things. She just wanted to pick out a few specific activities that she knew she would enjoy and spend the remainder of the time resting, enjoying lengthy meals, and beating to the tune of her own drummer.

Which is exactly what I’m doing in Praha. Who cares that I traveled thousands of miles to be here? This is my trip and I am spending it exactly how I want. Which includes a fair amount of wandering, a fair amount of writing in cafes, a fair amount of lengthy meals, a fair amount of enjoying my lavish hotel, and just a little – but not so much – of the really touristy stuff.

I’ve been here for three days, and for me, the jury’s still out on Praha. It is unquestionably beautiful, quite unlike any other city I’ve seen in my life. But it’s a dark beauty, with an unshakeable heaviness to it. There’s something formidable and slightly ominous that pervades through the steep hills and the narrow cobblestone streets and the hearty, heavy food, and the quietly dignified people and the gothic spires that extend into the wintry grey sky.

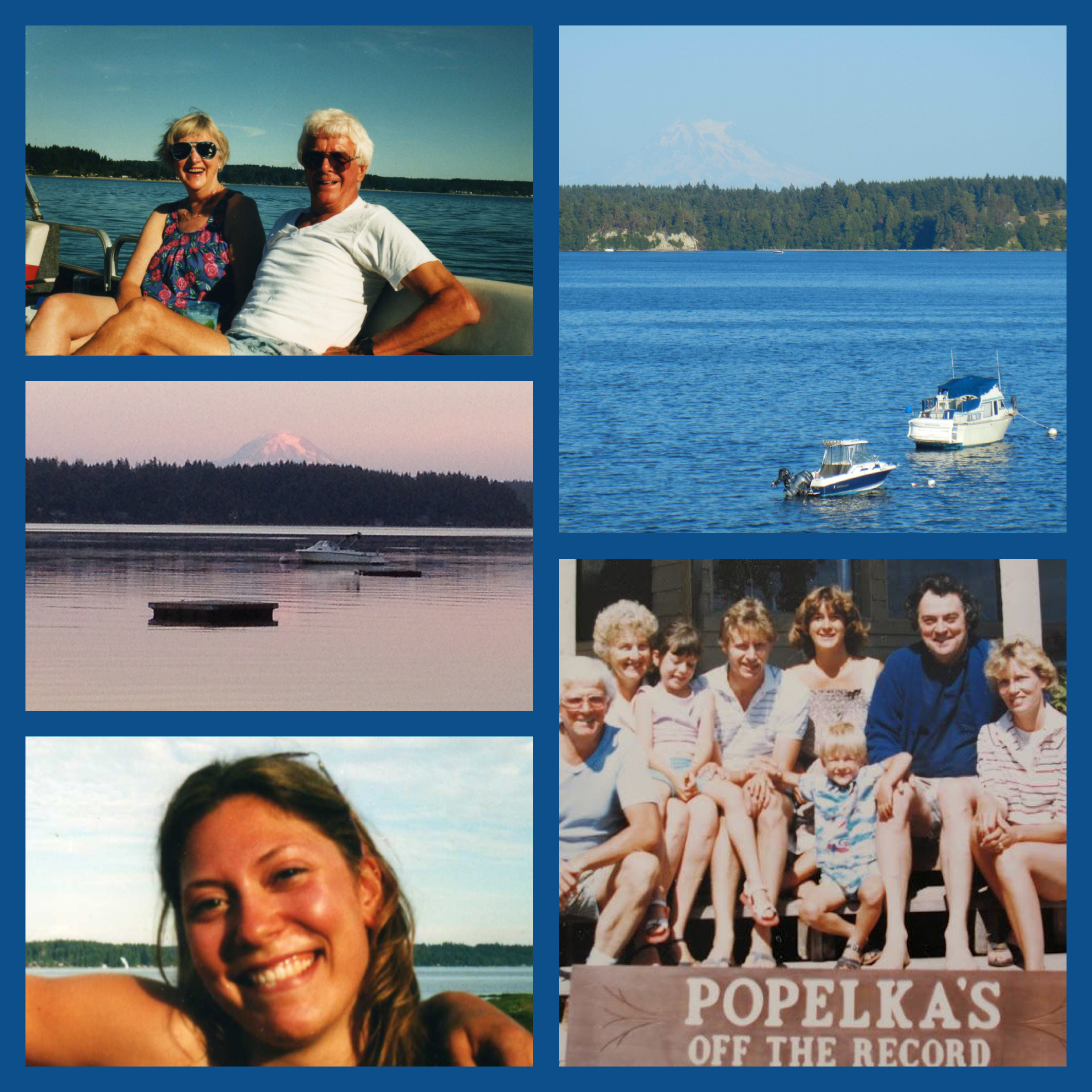

When I first decided to come here – inspired by my Grandpa Popelka’s Czech heritage – I had certain ideas about what this trip, what this place, would be like. It turns out that Prague, like all things in life, is very different than the picture I had in my mind of what it would be. But also as in life, it’s quite curious what we find when we don’t go looking for it. Like the fact that within this cold, dark, place, I have found a surprising amount of light. Both within my heart, and within my writing. Curious, indeed.

So thank you, Praha. Here’s to 2 ½ more days of embracing your mysterious beauty. Here’s to one more day after that in London, here’s to the long journey home to Los Angeles, and here’s to the even longer journey of finding a more permanent home, when I’m done with all the wandering.

Until next time, friends.