For most of my life, I had a complicated and difficult relationship with my father. He was a charming and brilliant man, a career-obsessed and highly successful trial lawyer, and a lifelong alcoholic.

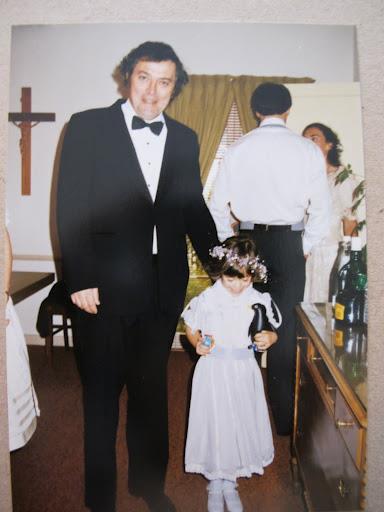

My Mom often told me that when she met my Dad, he swept her off her feet. She was a young, pretty court reporter living in Seattle and Dad, twenty-two years her senior with a legal practice in Anchorage, Alaska, was confident, handsome, and driven. She’d never met anyone like him before, and he made her feel like she could do anything. So, undaunted by their age difference and the fact that he had four children in their teens to early twenties from his previous marriage, she married him and moved to Alaska. A year later, I was born, their only child.

Anchorage was a magical, wonderful place to grow up. I remember Mom waking me up in the middle of the night to catch a glimpse of the Northern Lights streaking the sky a brilliant emerald green, feeding apples to an enormous moose out of our car window on more than one occasion, ice skating, sledding, and snowball fights in the winter, and long summer nights when it never seemed to get dark and I was allowed to stay up way past my bedtime.

But for my Mom, Anchorage was a dark and depressing place. My Dad was often away on business, and when he was home, cocktail hour would stretch on for hours, often ending in screaming matches between the two of them. I wasn’t old enough to understand everything that was going on, but I knew that my Dad was often drunk and that my Mom was sad, and I blamed him for it.

When Dad reluctantly closed his law practice due to his declining health, we moved to Olympia, Washington to be closer to my Mom’s parents. But retirement wasn’t good for Dad. The law was the only thing he ever really loved, that and sports – something we share – and depressed and hobbled by increasingly severe hearing loss (the unfortunate side effect of medication he’d taken to save his life during a childhood illness), he retreated into himself and he drank more than ever.

I got through high school by keeping as busy as I could. My grades were perfect, I sang in the choir, wrote for the school paper, and stayed out of the house as much as I could. I almost never invited friends over because I never knew what shape Dad was going to be in.

When I was accepted to USC, I jumped at the chance to get away. I’d had enough of the drinking, the depression, my Mom’s tears and the fucking Olympia rain. The bright lights and the big city were calling. I moved to Los Angeles, found jobs in the summers so I could stay, and I never looked back.

It’s funny how as you get older, life has a way of knocking you around, shifting your perspective, and making you less rigid and less sure of what you thought you knew. I had my own hardships – I suffered greatly in my first few years as a young actress trying to make it in L.A. I was broke, I was depressed, I couldn’t get a break, and with all of my college friends starting ‘real’ careers, I felt so, so alone.

My Mom worried about me and encouraged me to pursue a more stable career. My Dad never did. Ever the trial lawyer, he’d engage in a series of probing and uncomfortable questions about my life – something my siblings and I refer to as being ‘put on the witness stand.’ I’d explain to him how hard it was to break into the business, and his response would always be, ‘Well then you’ll just have to work harder.’

That was the thing about Dad. He was a gambler, a risk-taker, and he loved a challenge. The guy who often said, ‘I’d rather be lucky than good’ (but really, he was both), who put himself through law school by playing poker, who offered up thousands of dollars of his own money taking cases to defend clients who’d been victimized by insurance companies and large corporations, David versus Goliath type cases that no one thought he could win (and win, he did, in sometimes spectacular fashion), this was a man who didn’t believe in quitting. He was tenacious, he was a fighter, and when he told me that I’d ‘just have to work harder,’ I’ll be damned if he wasn’t always right.

Even before he was diagnosed with the pancreatic cancer that eventually killed him, I knew something was wrong with my Dad. He lost weight, his skin was sallow. He was still as mischievous as ever, but he’d lost a little bit of his edge. The twinkle in his eye faded.

He was nearing 80 years old and becoming frail, and I suddenly realized my Dad wouldn’t be around forever. I softened my stance. I came to grips with the fact that it was unfair to blame him for choosing alcohol over his family. It wasn’t a choice, it was a disease and holding on to my anger about it was only hurting me. The truth was, he’d never been mean. Though at times he was maddening, he was kind, generous, and I never doubted that he loved me. I chose to forgive him, and it made me free.

In her beautiful book The Rules of Inheritance, Claire Bidwell Smith writes about the death of both of her parents, her mother during her teenage years, and her father several years later when she was in her mid-20’s. Like me, she had a much older father and grew up closer to her Mom. But in her book, she makes a striking admission and it’s this: that if she had to lose both of her parents, she was glad that her Mom went first, because otherwise she would never really have gotten to know her father.

It’s difficult for me to admit this, but I feel the same way. Though my parents’ deaths were only four and a half months apart, and though my Dad was very sick – and often stubborn, maddening, impossible – I cherish those last months I had with him. We talked on the phone nearly every day. He told me was lonely, but that he was grateful for his children, that he loved us so very much and that we were getting him through. We talked about football. We talked about how much we missed my Mom.

When I visited him in Olympia, he was kind and sweet to me, and so appreciative of little things like when I’d hold his arm to steady him when he was having trouble walking. During the last Christmas we spent together, cheering the Seahawks on to victory against the hated San Francisco 49ers, Dad turned to me and said, ‘I think we’re good friends now, Sar.’ ‘We are, Dad,’ I agreed. He grinned.

At a reception in his honor following his funeral, one of his lifelong friends read Dad’s favorite poem, If, by Rudyard Kipling. It’s about living life boldly without fear of what others think of you, and without fear of loss. It’s how my Dad lived his life.

As much as I adored my mother, I can’t help but feel grateful for all of the gifts I inherited from my father. A lot of the things I really like about myself are pure Dad. I’m tenacious, I’m tough, I believe in fighting for the underdog, and –most importantly, and something I’ve leaned on in the last year and a half of my life – I possess the ability to remain cool headed in a crisis, and to laugh in the face of things that make others weep. It all stems from my Dad’s view of the world: that life is an adventure not to be taken too seriously, that obstacles are just exciting challenges to be met head on, and that no matter what life throws at you, everything always has a way of working out.

One of the last times I talked to him – before he was too sick to talk – was last year after our beloved Seattle Seahawks suffered a crushing loss to the Atlanta Falcons in the playoffs. While I was down and depressed, Dad barely seemed discouraged. ‘Sar, listen,’ he said, his voice full of excitement. ‘I’ve been watching these guys. They’re really good. They’re going to be good for a very long time. We’ll get ours.’ A couple of weeks ago, when we finally did get ours, I couldn’t help thinking that my irrepressible father had something to do with it.

In the same way that I can laugh in the face of things that make other people weep, I don’t think it’s a bummer that my Dad died on Valentine’s Day. I think he did it on purpose. Now my siblings and I have a forever reminder of him on a day that’s all about love. And I think that’s kind of sweet.

So Happy Valentine’s Day, Dad, you charming, insufferable, wonderful, impossible, lovable Irish rascal. I miss you. I love you. And I’m so grateful that I’m your daughter.

P.S. – I’ve pasted Dad’s favorite poem below, if you’d like to read it. It’s pretty great.

Until next time, friends.

If—

BY RUDYARD KIPLING

(‘Brother Square-Toes’—Rewards and Fairies)

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!